Anthony Glasby slept in his car.

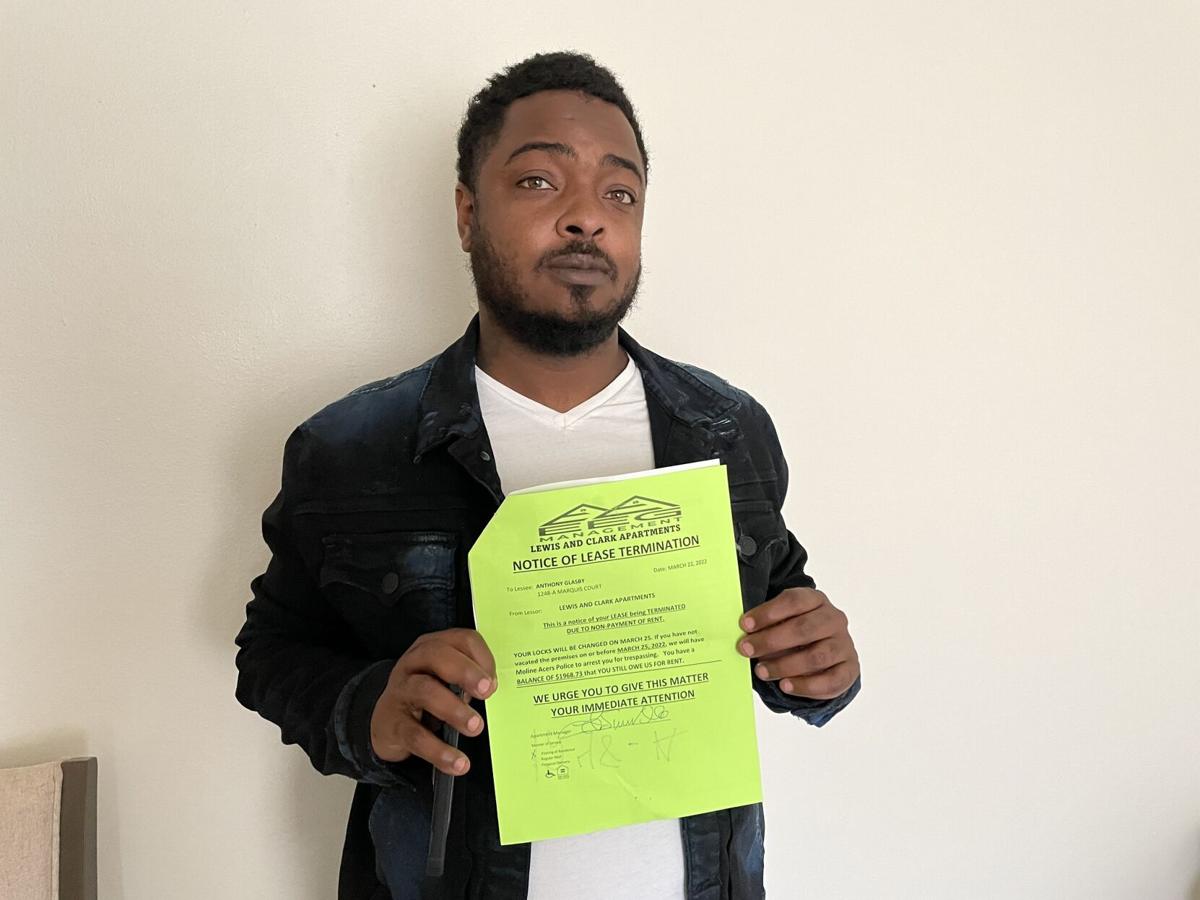

It was Tuesday night, April 5, and he had returned home from work a little after 11 p.m. to find the locks changed at his apartment. Glasby lives in the Lewis and Clark Apartments in Moline Acres. He has a good job as a COVID tech. He has a valid lease. He hasn’t been served any eviction papers. But the manager of the apartment complex called that day to tell Glasby he would be locked out of his apartment if he didn’t pay $517 in rent, a portion of his arrears. He didn’t have the money. When he came home from work his key didn’t work.

It was late, and he was tired. So he reclined the front seat in his 2016 Nissan Altima and fell asleep.

“I was terrified,” Glasby says. “I was waking up every 5 or 10 minutes it seems like, just to make sure I was safe.”

He slept in his car for two nights, and then spent one night at his aunt’s house. After payday, he paid a locksmith to change the locks, so he could get back into his home.

People are also reading…

Glasby knew the apartment complex was breaking the law, and that’s what he told the management of the complex. “If you’re evicting me, I need something in writing,” he told them. Indeed, under Missouri law, an apartment resident with a lease can’t be locked out or evicted without a court order.

That’s not stopping the owners of Lewis and Clark Apartments from kicking some of its residents to the street without due process, says Robert Swearingen, a lawyer with the nonprofit . After he was locked out, Glasby hired Swearingen to help him keep his apartment. So did Tamara Roseburrow, who was locked out of her apartment as well, allegedly because she was behind in rent.

Roseburrow was locked out twice. The second time, she called the Moline Acres police who stood by as a locksmith let her back into her apartment.

In reality, Glasby and Roseburrow, and others like them, should be the poster-children for how federal rental aid, passed as part of the American Rescue Plan, was intended to keep people who lost jobs during the pandemic in their homes, while also making landlords whole.

In December, Glasby came down with COVID. He was unable to work for more than a month and a half; later he lost his warehouse job because of his lack of vaccination. When he fell behind in rent, in January, he went to the management and made arrangements to pay what he could, so he didn’t fall too far behind. He paid $300 one week and $400 another, after receiving a notice from the complex threatening a lockout if he didn’t pay $1,968. But Glasby kept falling behind. In March, he and the landlord — the apartments are managed by a company called EEG Management based in New York — applied for rental aid through the , which served as a pass-through for the federal money.

That application was being reviewed by the state when Glasby was locked out of his apartment. In Roseburrow’s case, her aid from the same program had already been approved. She was locked out even though the landlord had been paid in full. Currently unemployed, she’s afraid to leave her apartment these days, worrying that she will come back and find she’s been locked out.

“This is their business model,” Swearingen says of the landlord. “They are like the worse debt collector you’ve ever seen.”

During the pandemic, while there was a national eviction moratorium, and similar moratoriums in the ������Ƶ region, some landlords got around the law by forcing out tenants in this same fashion, says fellow legal aid lawyer Jake Aubuchon. It’s an insidious way to take advantage of poor people. Unless a county or municipality has a law on the books that makes such lockouts criminal offenses — like in Maplewood and ������Ƶ — tenants have little recourse other than to file a lawsuit.

“It’s a legal fiction,” that landlords can simply lock out tenants without a court order, Aubuchon says, but increasingly, that seems to be a strategy the worst landlords are following. In Moline Acres, it’s “technically not a crime,” Aubuchon says. So what do tenants do? “They’re helpless.”

formed in early 2020 according to New York Division of Corporations records. The company formed a limited liability company in Missouri later that year called Lewis and Clark MO LLC. That company bought the apartment building in Moline Acres in 2020 from its previous owners. According to the company’s website, it owns or manages apartment complexes in Missouri, Illinois, Alabama and Mississippi. The complex manager and EEG Management didn’t return multiple phone calls and emails seeking comment.

Before she hired Swearingen, Roseburrow filed for a protective order in ������Ƶ County Circuit Court to try to stop the landlord from locking her out. Now the legal aid lawyer is going to press the case, and is considering filing a similar motion on behalf of other clients, like Glasby, who have been locked out.

In the meantime, Glasby goes to work every day not knowing if he’ll come home to a locked apartment. He’s looking for a new place to live. Swearingen and Aubuchon have called the apartment manager and the landlord to try to resolve the situation.

“Most landlords you call, once you explain the law, they agree not to lock out your client,” Aubuchon says. “Not here.”